Rare Bible Collection at the Museum of Biblical Art

One of the many shelves in the collection.

“We collect one book,” said Dr. Liana Lupas as she opened the door to the library. The Rare Bible Collection at MOBIA (Museum of Biblical Art) belongs to the American Bible Society. It is not open to the general public, but it can be visited by appointment. I happened upon it last Saturday when the curator, Dr. Lupas, was gone for the weekend. The museum attendant gave me a card and said I could contact Dr. Lupas directly for an appointment. It was a long shot, knowing a visit would have to happen today, I was afraid I may not get to see it. Dr. Lupas called this morning and told me I could come visit today. And now, here I was only a couple hours later, standing before one of the largest and finest collections of rare bibles.

Dr. Lupas is as rare and extraordinary as the collection she curates. She is soft spoken and chooses her words carefully. But she also has no qualms about correcting my Latin pronunciation. “I would say ‘poliGLOta,’ not ‘poLIglota,'” she points out later on as I read the spine on one of the bibles. Eventually she informs me it’s pronounced “prinKeps,” not “prinSeps” (at least I got “editio” right). But somehow I don’t feel belittled or embarrassed, I’m just incredibly grateful she’s giving me so much of her time. She doesn’t offer much information about herself, but when I ask, I learn that her PhD is in Classics (Greek and Latin), that she taught for 21 years at the University of Bucharest, that her mothertongue is Romanian and that she has been the curator of this collection for some 23 years. From my time with her, I deduce that she speaks at least six languages (Romanian, English, French, Spanish, Greek and Latin), but I wouldn’t be surprised if she actually speaks six more.

The 1440 Wycliffe manuscript is the collection’s most valuable book.

There are at least 7,000 languages spoken in the world today and the Bible is available in at least 2,600 of those. I’m surprised, I expected the second number to be higher, especially since she’s just told me it’s the most translated and reprinted book of all time. And then she explains that even though 2,600 is only a little over a third of the world’s languages, at least 96% of the world’s population have access to a Bible in a language they can understand. You see, there are languages with fewer than one hundred surviving speakers. These are languagues that will soon disappear. And many of these disappearing languages have portions of the Bible available to them, just not the Bible in its entirety (Hebrew and New Testaments). She tells me there is a consortium of Bible translators, the purpose of which is to produce a translation in any language that has at least 100,000 speakers. It seems like a big number at first, but that’s barely one tenth the population of New York City! Speaking of numbers, Dr. Lupas’ collection contains 46,000 specimens. That’s also the number of taxi drivers in New York City, by the way (and can you believe that only 170 of them are women?). That’s a lot of bibles.

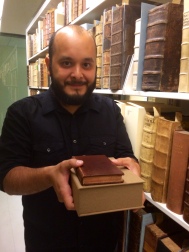

If I look nervous, it’s because I am holding the most valuable books in the collection.

Right around this time, Dr. Lupas asks me to leave my back pack behind and directs me to a staircase, “Wait, there’s more?!” I wonder. This whole time, we’ve only been looking at one third of the collection, there’s a whole other floor. When we get to the second floor, she explains she is now going to show me the rare bibles. I feel like I’m in a movie as she scans her badge, there’s a beep and a click and she opens the door to a temperature-controlled room. My heart starts beating faster, I’m about to be in the presence of old bibles. Really. Old. Expensive. Bibles. We begin at the very back of the room, where she pulls a small box and a small bible off the shelf. “These two are insured for one million dollars,” she tells me. I ask if I can take a picture of her holding them. She says, “No, you hold them and I’ll take a picture of you as a millionaire. And then you give me my million back” I hand her my phone, she gives me the precious books, and in her best teacher voice admonishes me, “With both hands!” I return the books as soon as I can, they’re making me nervous.

Dr. Lupas shows me her favorite Bible, the Complutensian. I asked why it’s her favorite and she simply replied, “I love it.”

We walk over to a table with a pillow. Dr. Lupas opens the box and out comes a 1440 Wycliffe manuscript, which she carefully places on the pillow and begins to open. This is the most valuable Bible in the collection, but she doesn’t handle it the way you handle a delicate and expensive artifact. No, she handles it like its a faithful, long time friend…with love. My bible knowledge is very rusty, but I know enough to remember John Wycliffe as a precursor to the Protestant Reformation who among other things proposed translating the Bible into the language of the people. I mention remembering he got himself into a lot of trouble for his translation work. She corrects me again, “Well, no he didn’t. You’re thinking of Tyndale, that’s this other book. Although they did dig Wycliffe up after and burned his bones.” “Of course, Tyndale, that’s what I was thinking!” I add, in an effort to save face. She turns a few of the pages and allows me to take a photo here and there. It is a glorius book, and it is in perfect condition. I almost can’t believe I’m inches away from a Bible that’s over 500 years old. We move on to the smaller book, the 1530 copy of Tyndale’s Pentateuch, printed in Amsterdam. It was William Tyndale who was convicted of heresy and burned at the stake.

The Tyndale Pentateuch, 1530.

The collection owns very few manuscripts and they have mostly been acquired as gifts. I ask why that is and Dr. Lupas explains that the mission of the collection is to document the history of Bible printing, publication and translation. In the time that she has curated this collection, Dr. Lupas has added around 600 languages to it. I ask whether the fact that there are so many new translations being produced over the years presents any problems or challenges for her. Without skipping a beat she replies, “No. I’m a collector.” I tell her I’m familiar with a few of the translations, and I rattle them off, thinking I can impress her. “The New Revised Standard Version, the King James (obviously), the New International Version, the New American Standard Bible, you know, most of them, right?” “Well,” she tells me, “if you count everything, there are at least 900 translations in English alone.” Not. Even. Close. I wonder if that’s a problem, or maybe even just strange – so many translations in just one language? Why? And she tells me these translations reflect the evolution of the language. That makes so much sense, the language is alive, word meanings change, words fall out of use, and so on. But, shouldn’t there be at least one authoritative translation? “There’s a Bible for everybody,” she responds.

La Biblia del Oso.

I tell her I grew up with the Reina-Valera, does she have any editions of that. “Of course,” she says. Of course. We walk over to another case and she pulls out a magnificent tome about the size a paver stone. “La Biblia del Oso,” she smiles. The Bible of the Bear? I’ve never heard it referred to that way. Well, that’s because I’ve never seen a first edition. She opens the Bible to the first page and there it is, a bear reaching up into a honeycomb on a tree. I ask why Valera’s name isn’t there. “Valera did next to nothing, Reina did all the work.” That would be Casiodoro de Reina and Cipriano de Valera. It turns out that Valera did a minor revision afterward, nothing really worthy of full partnership. The edition we’re looking at is from 1569, and it is absolutely beautiful.

“Let me show you my favorite Bible,” she says. Of course I want to see her favorite Bible! Biblia Poliglota Complutense (emphasis on the “glo”) or Complutensian Polyglot Bible, is a six volume edition, financed and produced by Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros in Alcalá de Henares. This is the first polyglot version of the entire Bible, published and printed by the Universidad Complutense around 1514 and 1517. On the page she has turned to, she points out the Hebrew on the right, the Greek on the left, the Latin vulgate in the middle, the Aramaic paraphrase in the bottom left and the Latin commentary in the bottom right. She explains the significance of this work; this is not just a translation of a holy text, “He wanted it to also be a manual for learning Hebrew and Greek.” The significance of this book is palpable, I feel like I’m looking at the Rosetta Stone of printed Bibles, and I’m at a loss for words. “Look at the typeface,” she says in the same tone a loving grandmother would show you a picture of her grandchild and proudly exclaim, “Look at those eyes.” These books, these bibles, they are her companions, her friends.

Biblia Poliglota Complutense

“What does it mean for you to be surrounded by all of these bibles, for this to be your work?” She looks around, then back at me and says, “Well, it means so much. It’s everything.” There’s a pause and I hope it wasn’t a wrong question to ask. Then she adds, “I’m 73, almost 74, and I don’t want to retire.” We’re back on the first level where she shows me a few oddities. A Spanish language Manga new testament, with Jesus illustrated as a Japanese superhero along with his disciples, stands out. “What? What is this? How strange!” I ask, hardly believing this is in the same collection as those centuries-old Bibles. She shrugs and says, “I’m a collector.” I can tell our visit is about to come to an end, she’s already been more than generous with her time. She says she has a couple more things she can show me. I tell her I’m happy to stay as long as she’ll let me, until she kicks me out. “Well, I have a lot of work. We all have a lot of work.” And I think by “we” she means her and the bibles.